Silk Road Trade & Travel Encyclopedia

丝绸之路网站(丝路网站)

丝绸之路百科全书—游客、学生和教师的参考资源

İPEK YOLU ve YOLLARI ANSİKLOPEDİSİ

Silk Road Trade & Travel Encyclopedia

丝绸之路网站(丝路网站)

丝绸之路百科全书—游客、学生和教师的参考资源

İPEK YOLU

ve YOLLARI

ANSİKLOPEDİSİ

一 To Start Your Silk Routes Journey

CLICK

on a Letter from the Alphabetical

Glossary

一

A B

C

D

E

F

G

H I

J

K

L

M

N O P

Q

R

S

T

U V

W

X

Y

Z

Artifacts & Museum Displays

A

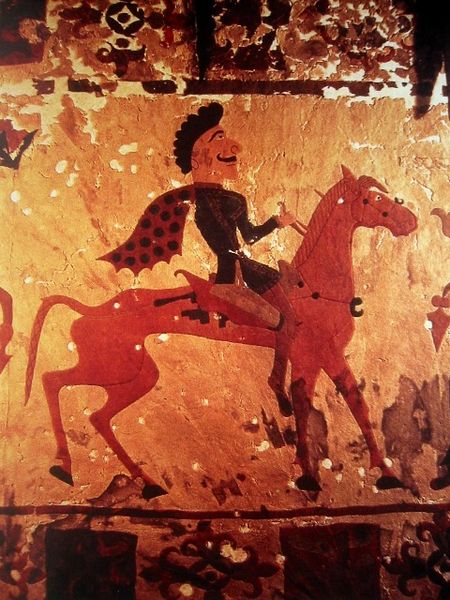

Scythian

horseman from the general area of the

Ili river,

Pazyryk,

c.300

BCE.

Detail from a carpet in the State Hermitage Museum in St Petersburg, Russia.

The Topkapi Palace in Istanbul, capital of the Ottoman Empire, contains a vast collection of Chinese celadon porcelains which were valued by the sultans for their beauty. Above, a celadon dish from the Yuan dynasty, now part of the collection of the Topkapi Museum. Chinese celadons were carefully transported along the dangerous silk routes and presented as gifts by Chinese rulers. Celadons were imitated in Iran, with turpuoise glaze and fish motifs, during the 14th century. For centuries, various designs were modeled on much-sought after precious Chinese porcelain. The Ottomans imitated and used Chinese motifs, such as blue and white cloud bands, on the their Iznik wares, particularly between the 15th and 16th centuries.

A late Zhou Dynasty or early Han Dynasty (c. 300–200 BCE) Chinese bronze mirror inlaid with glass and showing influence from Hellenistic civilization in Central Asia. Victoria and Albert Museum.

Portion of woven silk textile from Tomb No. 1 at Mawangdui, Changsha, Hunan province, China, dated to the Western Han Era, 2nd century BCE.

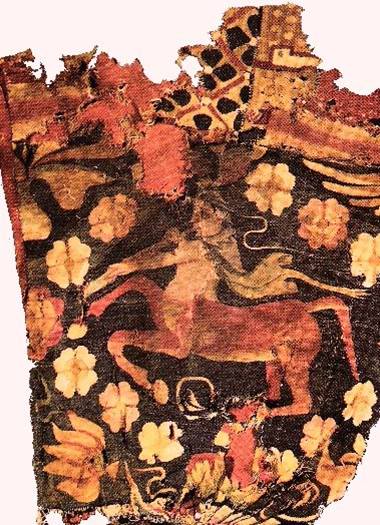

Sampul tapestry ca 300 BC. Xinjiang Museum, Urumqi, China

Chinese

jade

and

steatite

plaques, in the

Scythian-style

animal art of the steppes. 4th–3rd century BCE.

Special exhibition at the British Museum, August 2005.

Men with dragons. Gold artifacts of the Scythians in Bactria, at the site of Tillia tepe.

A Chinese Han Dynasty terracotta horse head (1st-2nd century C.E.). Musée Guimet, Paris.

A Chinese Western Han Dynasty (202 BC – 9 AD) bronze rhinoceros with gold and silver inlay. Beijing National Museum.

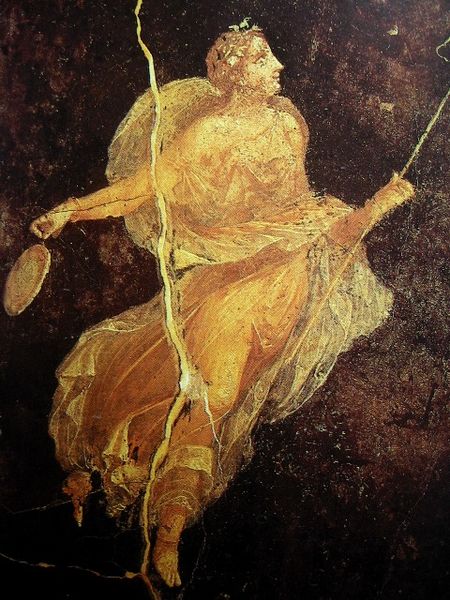

Maenad in silk dress. Naples National Museum.

Wall painting at Bezelik caves in Flaming Mountains, Turpan Depression, China, 5th to the 9th centuries.

A foreigner depicted as a camel driver; Chinese terracotta sculpture from the Northern Wei Dynasty (386-534 AD). Cernuschi Museum, Paris, France.

9th century fresco from the Bezeklik grottoes near Turfan,

Tarim Basin,

China.

The person to the left is an European/Western Asian trader or monk

(distinguishable by his red hair and full beard and face), to the right an East

Asian Buddhist monk.

Foreign Dancer (Huren wu yong). Terra Cotta with traces of polychromy. Tang Dynasty (618 – 907). Cernuschi Museum, Paris, France.

Italian pottery of the mid-15th century was heavily influenced by Chinese ceramics. A Sancai ("Three colors") plate (left), and a Ming-type blue-white vase (right), made in Northern Italy, mid-15th century. Musée du Louvre.

The Fra Mauro Map, Venice, 1459

The period of the High Middle Ages in Europe and East Asia saw major technological advances, including the diffusion through the Silk Road of the precursor to movable type printing, gunpowder, the astrolabe, and the compass. Korean maps such as the Kangnido and Islamic mapmaking seem to have influenced the emergence of the first European practical world maps, such as those of De Virga or Fra Mauro. Ramusio, a contemporary, maintains that Fra Mauro's map is "an improved copy of the one brought from Cathay by Marco Polo."

Silk Routes.net | Ipek Yollari.net